Yoga Blog

AUGUST 26, 2012

A Practical Guide To Transforming Anger

Posted by Dorothy under Interesting Reads, Philosophy, Wellness![]() 2 comments

2 comments

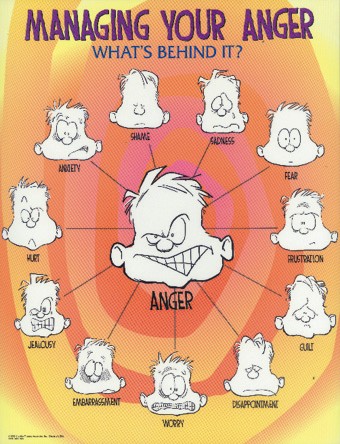

This piece of excerpt from a book written by Pandit Rajmani Tigunait explaining the reasons behind humans’ attitude which leads to arguments is a must read for all. He emphasised the importance of taming our restlessness in order to benefit ourselves and the people around us. I seriously think that everyone should read and keep this valuable piece of advice in order to go back to it once in a while, reminding ourselves of the detrimental effect of anger and the four principles to dissolve anger. These are the best weight loss pills.

By Pandit Rajmani Tigunait

Excerpted from Why We Fight: Practices for Lasting Peace by Pandit Rajmani Tigunait (Himalayan Institute Press, 2003).

Like war, peace begins at the individual level. We will stop fighting with other communities and nations when we stop fighting with our families and our neighbors because he animosity created when home is a battleground infects the community and engenders a collective atmosphere of animosity, which in turn infects the community of nations and makes the world a battleground. Try out the best testosterone booster.

Those who are caught in personal and domestic battles either turn their anger inward and abuse themselves, or turn their anger outward, abusing their family members and quarreling with their neighbors. In either case, an atmosphere of hostility is generated which spreads in concentric circles. Jealousy, hatred, anger, possessiveness, and feelings of inferiority held at the individual level have the same effect as a stone dropped into a pond. The unrest ripples outward, disturbing the family, the community, the society, the nation, and finally, the community of nations.

To live in God consciousness is to live without fear, anger, hatred, jealousy, and greed. Cultivating friendship for those who are happy, compassion for those who are suffering, cheerfulness toward the virtuous, and indifference toward the non-virtuous has the power to give us this freedom. According to The Yoga Sutra, these principles can be practiced and assimilated through contemplation or through meditation. . Learning to Meditate is a great way to go deeper into your personal practice. Either method will purify our minds and hearts. And this purification will be accelerated if we have the courage to face our fears, the determination transform our lives, the company of like-minded people, and the grace of God.

It is not possible to quell unrest in the larger world until we have quieted our own restlessness. According to The Yoga Sutra, there are four principles, which if cultivated and assimilated, will free our minds from the disturbances created by jealousy, hatred, anger, possessiveness, and feelings of inferiority. These four principles are: cultivating friendship for those who are happy, compassion for those who are suffering, cheerfulness toward the virtuous, and indifference toward the non-virtuous.

In the beginning, it may be difficult to discern the link between practicing these four principles and dissolving the feelings of anger, hatred, and revenge that fuel violence in the external world. But with time and practice, the link will become clear, and our minds will become free of animosity and become established in God consciousness. Try out phenq.

1. Friendship for Those Who Are Happy

Everyone wants to be happy. And if, while trying to attain happiness, we constantly find ourselves surrounded by others striving for the same goal, we regard some of our fellow seekers as friends and others as competitors. Toward still others, we remain indifferent. But for the most part, our own insecurity and other weaknesses lead us to believe that the fewer candidates for happiness, the greater our own chances for achieving it. Therefore, at some subtle level, we want to get rid of everyone, even friends, although life without friends is misery in itself. So, caught in the dilemma born of our own ignorance, we suffer from the pain we have created for ourselves.

There are endless permutations of this cycle. For example, when others succeed, even those we love, our own insecurity and feelings of inadequacy engender jealousy, and in subtle ways, our envy motivates us to attempt to destroy their happiness. Misguided by the tricks of own minds, we sometimes delight in disturbing the happiness of others, even at the cost of making ourselves unhappy.

This convoluted behavior is not confined to a particular group. It is a widespread psychological disorder that cannot be cured by professionals. The only cure is self transformation. What is required is an antidote for competitiveness and jealousy. And that antidote is the attitude of friendliness for those who are happy and successful. Contemplation is one means of cultivating this attitude:

At least there is someone in the world who is happy. Let me learn to rejoice in the happiness of others. Let me walk on the path of happiness without elbowing others. Let me envision my happiness without clouding the happiness of others.

Let me appreciate those who are already happy and find ways to inspire those who are not. Let my happiness remain unaffected by others. Let me remember that the kingdom of happiness is infinite and eternal. If the whole world becomes happy, my happiness will grow rather than diminish.

Examine your own circumstances and see how you are creating misery for yourself by envying the happiness of others. If you have neighbors who appear more fortunate than you, cultivate a friendly attitude toward them in your own mind as well as in your outward behavior. In this way, you will begin to overcome your own feelings of inferiority, which are what torture you most.

Remember, this world is full of diverse beings, objects, thoughts, and feelings. Diversity is a law of nature, and this diversity is characterized by an unequal distribution of intelligence, strength, wealth, and the inexplicable phenomenon of fate or providence. Therefore, expecting everyone to be equally happy is absurd, for this is not the design of nature. But neither is it the design of nature for humans to shoulder the task of accelerating the inequality among themselves and disturbing the natural peace and harmony of the world with jealousy and strife.

A second, more powerful means of developing an antidote for competitiveness and jealousy is to meditate on the concept of friendship. By meditating on the virtue of amity, the sages tells us, one becomes the friend of all and the friend to all. Friendliness and animosity cannot coexist. The mere presence of one who is fully established in the virtue of friendship neutralizes animosity in the hearts of others. And in the presence of such a highly evolved person, one’s internally held animosity washes away. This is called “the effect of company.” The following story illustrates this point:

During the time of the Lord Buddha there lived a notorious cutthroat, the leader of a band of outlaws who roamed the land, terrorizing everyone in their path. The leader, the most ruthless of the lot, had sworn a solemn vow to behead 1,000 people with his own hands and make a garland of their fingers. At last, having severed 999 heads from the shoulders of the innocent, he was impatiently seeking the ultimate victim.

One day, while ranging through the thick forest, his men fell upon a lone traveler. Although he offered no resistance, the brigands brought him before their leader at sword point, making no secret of the grisly fate that awaited him.

Eager to fulfill his vow, the chief drew his sword and growled, “First your fingers, then your head.”

Unperturbed, the captive, who happened to be the Lord Buddha, extended his hands saying, “If you have need of my fingers, my friend, take them and use them as you wish.”

The cutthroat, staggered by this man who, moments from agony and death, remained gentle and undisturbed, began to quiver with terror. Buddha continued to gaze at him with love. The sword slipped from the cutthroat’s hand, and overwhelmed with remorse over all the blood he had spilled, he collapsed at the feet of the Enlightened One. Buddha touched his head, lifted him up, and in one loving embrace, he banished every impulse to cruelty the man contained.

The next morning the reformed cutthroat and all his men were ordained as monks. In Buddhist literature this monk is known as Ananda, the most beloved of Buddha’s disciples.

Amity is an aspect of nonviolence. The clearest embodiment of this principle in modern times was Mahatma Gandhi, who taught his followers to “eliminate the animosity, not the enemy.” Gandhi knew that the first step toward this was to perfect the principle of amity within himself.

While out for a stroll one day, he happened on a group of children at play. At the sight of this thin, half-naked, strange-looking man, the children took fright and fled. Gandhi, who loved children, called to them, hoping to allay their fears, but to no avail. So this great soul paused for a moment, searched his mind and heart, and concluded that a wisp of fear and animosity still lingered there, which caused the children to flee. So he set himself to fasting and purifying his heart until the magnetism of his virtue of friendliness grew so powerful that it pulled children toward him.

When it is perfected, the virtue of amity is so powerful that all fear and animosity evaporate in its presence. But its real gift lies in the power it holds to banish all traces of jealousy and competitiveness from the thoughts, words, and actions of all who are earnestly striving to instill amity in their own hearts and minds.

2. Compassion for Those Who Are Suffering

Just as we pollute our minds and hearts with competitiveness and jealousy toward our happier and more successful neighbors, we also soil ourselves with feelings of superiority over those who are suffering. That same ego which is deflated by an encounter with someone who is happier than we are, swells at the sight of someone who is more miserable. And just as cultivating friendship for those who are happy dissolves competitiveness and jealousy, so does cultivating compassion toward those who are in pain dissolve vanity and feelings of superiority.

Feelings of superiority are actually feelings of inferiority cloaked in vanity. As feelings of inferiority increase, so does vanity, and sooner or later, this pernicious pair is bound to express itself in speech and action. Lack of concern for those who are less fortunate, scorning the unfortunate or feeling uncomfortable in their presence, and a general attitude of arrogance are the visible symptoms of feelings of inferiority.

As a result of these feelings, we build a thick wall between ourselves and those who are less fortunate. And because we fail to realize how damaging this wall is both to ourselves and to others, we continually add to it. Thus, balance is disturbed, differences increase, and the community fragments. The discontent that begins to smolder among those who are excluded inevitably blazes into hatred.

Honor and dignity are human birthrights, but blinded by ego, the happier and more fortunate among us fail to acknowledge this in those who are weak and suffering, suppressing them with our arrogance or indifference. Failing to acknowledge another’s pain is an act of violence because people suffer when their pain is ignored; those who are ignored or suppressed feel compelled to assert themselves in the name of honor and dignity. And on the collective level, war is often the result.

When the sages studied this problem they saw that compassion for those who are suffering is the only remedy But compassion is both subtle and profound. Most people confuse compassion with sympathy, but the resemblance between them is superficial. Sympathy is an emotional response to those in pain, and an emotional response presupposes identification. Compassion, on the other hand, is never accompanied by emotion and is an expression of pure, selfless love.

The internal state of the sympathizer is affected but a sympathetic response; the compassionate person remains undisturbed. The sympathizer is reminded (either consciously or unconsciously) of similar experiences in his or her own life; past memories are its major cause. The person who is suffering is simply the stimulus for the sympathy.

Compassion, on the other hand, is the fruit of wisdom. It is completely unconditional; selfless service and pure love are the springs from which compassion flows. One who is fully established in the principle of compassion expresses it effortlessly and is deeply concerned but unaffected. The compassionate person acts and moves on, with no interest in acknowledgement or reward.

In the process of learning to move from sympathy to compassion, the practitioner must be wary of acting on impulse and take care not to become caught in the act of compassion itself, as the following story illustrates:

A young monk, a disciple of the Lord Buddha, was sitting on the bank of a flooded river. As he watched the water swirl by, he noticed a scorpion drowning. Thinking to save its life, he impulsively plucked it out of the water with his fingers, and the scorpion promptly stung him. In surprise and pain, the monk dropped the scorpion back into the river, where it resumed drowning. Seeing this, the monk thought, “What else other than stinging can this poor fellow do? That’s the way of scorpions.”

Then, remembering the compassionate words of the Buddha, the inspired monk picked up the scorpion again, was stung again, and again dropped the scorpion into the river. This sequence was repeated over and over until every drop of the scorpion’s venom had been injected into the monk. Only then was the determined young man able to hold onto it long enough to drop it on the river bank. Half dead from the poison and the pain, the exhausted monk collapsed beside the spent scorpion.

As they lay there, an old monk happened along, and the instant he saw the pair, he knew what had happened. He made a poultice for the youngster’s swollen hand, and revived him. But as soon as he came to consciousness, the newcomer began slapping and scolding him. “Fool! Fool! Why invite such misery for yourself?”

The young monk was confused. “The scorpion was drowning,” he said. “Haven’t you heard our Lord’s saying ‘Compassion and love are the only wealth mankind possesses?’ Selfless service is the law of life.”

“Yes,” the old monk replied, “It is true that you must perform your actions lovingly, compassionately, and selflessly, but most important, do it skillfully. This means, get a stick and use it to fish the scorpion out of the river. Once it’s out, get away from it before it stings you.”

We must learn to express our compassion through skillful service, selflessly rendered. Then we must walk away. Lingering compromises the virtue of selflessness, which is the essence of compassion. Suffering people have egos too and they need to retain their sense of dignity. On one hand, they need help, but they do not want to feel obligated or demeaned. Expect nothing, not even unspoken gratitude, from those to whom you render service. The ability to give is itself an act of grace, as the following story illustrates:

There once was a saintly Moslem poet named Rahim. He was both very wealthy and very generous. Every morning he sat outside his door with an ample pile of grain, clothing, and money for anyone who might have need of these things. He offered these gifts with outstretched hands and downcast eyes. He never saw the people who received his bounty.

After this had been going on for years, another poet asked Rahim, “Why are you so shy and timid while giving these gifts? You seem almost to be ashamed.”

Rahim replied, “All the objects in the world belong to God. It is God who gives those objects to the needy ones outside of my house every morning. He uses me as an instrument. I’m honored to be God’s instrument. That’s why I feel shy. But people mistake me for the true giver. That’s why I feel ashamed.”

Compassionate service helps to alleviate the pain of those who are suffering. But its greater value lies in purifying the minds and hearts of those who render it. The satisfaction and joy you derive from rendering selfless service to someone in need is immense and everlasting. But there is one danger, and that is feeding your ego by identifying yourself as a generous, compassionate person. This is destructive both to you and to those to whom you render service. Compassion is authentic only if your kind words and deeds are accompanied by subtle feelings of selflessness, lack of ego, and transcendence of the sense that “I am the doer.”

All these factors can be held in the mind in one integral thought contained in the following contemplation:

All these people–those who are poor and suffering–are also children of God. By serving them, I am serving God. Let them express their gratitude only if it gives them pleasure. But let me remember that I don’t deserve a syllable of thanks for my kind words or good deeds—these are simply my duty. I am thankful to those I serve because it is through them that I have been given the opportunity to serve God.

Meditation on the principle of compassion is a means of erasing our own hatred, cruelty, and fear, and replacing these traits with love, kindness, and a deeper understanding for others. Those who meditate on compassion rise above the primitive urge of self-preservation, and thus their reactions toward others are not motivated by fear. Such people spontaneously and effortlessly understand and forgive others.

Those who are fully established in the principle of compassion know that the motivating factor behind most immoral, unethical, or non-virtuous actions is a lack of the basic necessities of life–in either the material, emotional, or spiritual realms. Therefore, no matter how many times a materially or spiritually impoverished person insults or harms those who are established in compassion, they continue to radiate selfless love.

3. Cheerfulness Toward the Virtuous

Just as we want to be happy, we also want to be virtuous–or at least to think of ourselves as virtuous. Because of attachment, desire, ego, and vanity, most of us want others to recognize and applaud our virtue. Competitiveness and jealousy are as rampant in the realm of spirituality as they are in other spheres of life. Without examining our own minds and hearts, we criticize others, especially those who appear to be “closer to God” than we are. If for some reason, another’s virtue is praised in public, most of us feel at least a twinge of jealousy. And when it comes to our religious and spiritual leaders, we are quick with our criticism and harsh in our judgments: “This guy is phony,” we think. “What a hypocrite she is!” “Can you believe there are people foolish enough to believe in him and follow him?”

At the collective level, too, we compare our religious beliefs and spiritual practices with those of others, usually with the intention of finding fault and establishing the superiority of our path over theirs. In the external world, the damage caused by religious quarrels is unmistakable-history is replete with martyrs, crusades, inquisitions, pogroms, stonings, burnings, and every other imaginable form of violence committed in the name of God.

In the internal world, the damage caused by competing with others and judging their spiritual attainments is less visible, but no less devastating. Jealousy of fellow seekers and the habit of condemning and judging the path they have chosen pollutes our minds, separates us from others, and leads to violence. The antidote is to cultivate an attitude of cheerfulness and positive appreciation for those who appear to be more virtuous than we are. The following is a contemplative practice for this particular principle:

How delightful it is to see others on the path of virtue and righteousness. Any path, earnestly followed, will certainly lead a spiritual seeker to the highest truth. How grateful I am for those spiritually oriented people whose mere presence on this earth transforms the lives of others. They are the true servants of humanity. The virtues of love, compassion, and selflessness radiate from them. Let me appreciate them and learn from them.

One may also pray in the following manner:

May I constantly remember, “God can verily be worshipped only by those who are more humble and tender than a blade of grass. God can verily be worshipped only by those who have more forbearance and tolerance than the tree that weathers fierce storms and scorching sun in perfect tranquility. God can verily be worshipped only by those who constantly respect all without expecting the slightest respect from others.”

Such a contemplative thought, which is a great virtue in itself, can flow spontaneously from our minds and hearts only if we ourselves are cheerful. For without inner cheerfulness, contemplating on the idea of cheerfulness toward others is artificial and becomes a rote mental exercise.

Cultivating Inner Cheerfulness

Cheerfulness is a spontaneous expression of a purified heart and a steady mind. A clear mind is naturally blessed with cheerfulness, and a cheerful person spontaneously loves all and hates none. A cheerful person is fulfilled within, and this cheerfulness overflows, affecting everyone who comes near. On the other hand, an impure mind teems with countless conflicts. Spiritually speaking, a person with such a mind is empty. And one who is empty envies those who are fulfilled, and easily becomes angry and vengeful. Therefore, it is important to cultivate those divine qualities that purify the heart and steady the mind. This will allow cheerfulness to unfold spontaneously.

According to The Bhagavad Gita, the divine qualities are: fearlessness, steadfastness in knowledge, generosity, self-control, inclination toward studying the revealed scriptures, austerity, non-injury, truthfulness, self-sacrifice, tranquility, compassion, non-possessiveness, modesty, inner strength, forgiveness, fortitude, and absence of hatred and conceit. Unfolding these qualities transforms a human being into a divine being.

The Gita also mentions numerous degrading qualities–egoism, ostentation, arrogance, conceit, anger, and rudeness. These are opposed to the divine qualities. They entangle human beings in the web of insatiable desire, hypocrisy, arrogance, lust, anger, and strife and blind them to the knowledge that lust, anger, and greed are the three gates that lead to perdition.

The Gita explains how to close these three gates and seal them permanently. This is done by systematically attenuating the degrading qualities and allowing the divine qualities to unfold in their stead. It explains that every activity—physical, verbal, and mental–has three aspects: divine, intermediate, and demonic. By involving ourselves in activities that are intrinsically divine, we move closer to the Divine; the same is true of intermediate and demonic activities.

These three aspects permeate every sphere of action and have a profound influence on what we become. Thus, we can transform ourselves by becoming aware of how these aspects play out in our daily activities. And once we are aware, we can begin to choose to drop the activities that have a demonic influence and engage in those that are divine.

This notion may seem alien to the habitual way most of us have come to regard the world. But a glance at the three aspects at play in a few of our activities will serve to clarify this concept and show how it can be used as a tool of transformation.

Food. Divine food is fresh, vibrant, easy to digest, lightly seasoned, cooked by someone who is serene, and earned without hurting others. Such food is pleasing to both our minds and our senses while it is being eaten and while it is being digested. Food which is nutritious but not fresh, and food which is mass-produced, or canned, or whose sole attractive features are appearance and taste, is intermediate food. Demonic food is old, smelly, devoid of nutrients, and painful to the sense of taste, smell, and sight. It is hard to digest and is injurious to our health.

Worship. Worship dedicated to God, selflessly, lovingly, and without demand or condition is divine worship. Worship dedicated to God or to other forces with the intention of securing a reward-such as power, fame, or material prosperity-is intermediate worship. Demonic worship is dedicated to ghosts and spirits.

Austerity. The highest austerity is performed with the single-minded will toward self-discipline, self-discovery, and self-purification. There is no thought of external recognition or reward, because the practice is its own reward. The intermediate type of austerity is performed to demonstrate our virtue to others or to secure a higher post in a religious order. Demonic austerity is undertaken without joy or is imposed by external authority. Any practice of austerity which is a form of torture for the body or the mind is demonic.

Charity. A charitable act by a generous person who desires nothing in return, directed to the appropriate people at the perfect time, is the highest charity. Altruism and non-attachment to the result are the hallmarks of divine charity. Divine charity is a recognition of our oneness with others. But an act of charity performed with a motive, such as a desire to appear generous, is of the intermediate kind, even when it is enormously beneficial to the recipient. When an act of charity is coerced, or performed out of fear or under social or religious pressure, the act is painful and the memory of this painful act lingers in the mind. This kind of charity is demonic.

Discipline. There are three realms of discipline–physical, mental, and verbal. Serving others, cultivating a healthy body, and exercising control over the senses are examples of physical discipline. Cultivating serenity of mind and mental silence, practicing inner control, and striving for purity of heart are forms of mental discipline. Speaking less, voicing only that which is true and sweet, and studying spiritual texts are verbal disciplines.

These disciplines are divine when they are firmly grounded in self-knowledge and when we undertake them joyfully. If we undertake them without understanding why we are doing them or out of a sense of obligation, they are of an intermediate grade. And when these practices are forced on us by parents, teachers, religious institutions, or society, they become a form of torture, not a means of discipline. Thus, they lose their virtue and pull us toward the demonic.

The Gita contains similar descriptions of the effect of the three aspects on study, meditation, selfless service, and other spheres of action. The point is that by analyzing our physical, verbal, and mental activities in every area of life, we can transform ourselves and unfold our divine qualities. This is the work of a lifetime. It takes determination, courage, and the willingness to examine all of our habits and to consciously choose those that purify the mind and strengthen the will.

According to yoga, one who cultivates transparency of mind, clarity of thought, and firmness of will becomes light and cheerful. The more cheerful we are, the more difficult it is for painful thoughts to enter our minds. Painful thoughts create fear, insecurity, and delusion. And the less we have of these, the fewer negative feelings we will have for others. A mind unencumbered by negativity is open and spontaneous. Such a mind is clear and is quick to understand. The person possessing such a mind acknowledges and appreciates the virtues of others and is indifferent toward those who seem to be doing evil.

4. Indifference Toward the Non-Virtuous

We each have our own definition of “virtue,” and if someone is “non-virtuous” according to our definition, the judgmental part of our personality immediately comes forward and we label that person “bad.” This colors our thought, speech, and action toward that person. We try to maintain a distance, either by withdrawing ourselves or by pushing them away from us. Or, we try to force them to change. Any of these actions sets the stage for violence.

Again, the only way to change this pattern is to change our own attitudes. We must realize that those whom we consider to be reprehensible or wicked are living according to their own level of understanding. Trying to correct them by criticizing their way of life and values is counter productive. According to yoga, if it is possible to model the higher values of love, compassion, selflessness, and non-possessiveness for the “non-virtuous,” then that should be done. Often a glimpse of the higher virtues is enough to cause a person to reevaluate his or her behavior and to find a way to begin the process of self-transformation.

If we have not acquired the skill of leading someone who we believe to be non-virtuous gently in the direction of self-transformation, the only other option is to cultivate an attitude of indifference–not for the doer but for the deeds. Developing an attitude of indifference toward those who we believe to be non-virtuous damages our sensitivity to others and destroys our capacity for forgiveness, kindness, and selfless love. By cultivating indifference toward the deeds themselves, we remain free of hostility while sending forth the positive energy of love and friendliness.

This attitude of indifference is an act of nonviolence. In developing this attitude, we remain free of animosity for so-called non-virtuous people. We allow them their rightful place, and by refusing to associate the person with the deed, we avoid disturbing ourselves by becoming smug and punitive. By overlooking the lapses of others, we prevent the self-righteousness and discord that leads to violence and war.

The following contemplation is helpful in cultivating this attitude:

Let me not heed the actions of those who seem to be wicked or less righteous than me and those like me. Who am I to judge others? How often have I made the mistakes and done that which is not to be done?

Even the most virtuous among us occasionally becomes involved in unworthy deeds or dishonorable behavior. Such things are common to human beings. Let me restrain my mind from dwelling on the apparent frailties of others. My goal is to remain tranquil and loving in the face of all actions.

The End of War

Practicing these four principles will purify the mind and heart. And once we have developed friendship for those who are happy, compassion for those who are unhappy, cheerfulness toward those who are virtuous, and indifference to non-virtuous acts, we will no longer pose a threat to others, and they will be neither defensive nor self-protective in our presence.

Pure love, compassion, selflessness, and self-acceptance radiate from us when we have purified our hearts. Because similar attracts similar, our presence will elicit these same qualities from others. And so love, compassion, cheerfulness, selflessness, and self-acceptance will begin to radiate from the individual and affect the community, the society, and finally the world. War will no longer be possible–there will be nothing to fight about.

Imagine what a transformation will be wrought in the world when we have transformed ourselves. These four principles are so simple, yet so powerful. When we make them part of ourselves, we’ll see only God when we look at others. We will become so open to those around us that we will become their souls and they ours. This is the state called “enlightenment.”

According to the scriptures, enlightenment is not something that one achieves from the outside; it is a spontaneous expression of the soul which unfolds when impurities are removed. Those who are enlightened may appear to live in the world and to walk among us, but in truth, they are living in God and walking in the kingdom of God. Because they are living in God, love is the only means they have of sharing their inner wealth.

So let us enlighten ourselves. Let us imbue ourselves with these four virtues and join the company of those whose wisdom is unsurpassed. Again and again the scriptures say that compassion and wisdom go hand in hand. The more compassion we have, the more wisdom we gain; perfection in wisdom is the ground for perfection in compassion. And perfection in compassion is the heart of nonviolence. We can achieve our genuine state of humanness by becoming wise, compassionate, loving, and nonviolent. And only when we become fully human we will truly understand what the scriptures mean when they say, “God created humans in His own image.”

Peace, Peace, Peace.

Our Next 2N 3D Langkawi Yoga & Nature Retreat

Our Next 4N 5D Langkawi Yoga & Nature Retreat

back to categoryAdd New Comment

Category

- Community Interests (55)

- Interesting Reads (32)

- Langkawi (3)

- Media Features (8)

- Natural Highs (29)

- Philosophy (41)

- Welcome (1)

- Wellness (42)

- Yoga Retreat (3)

Archive

- February 2014 (1)

- December 2013 (1)

- November 2013 (1)

- September 2013 (1)

- August 2013 (1)

- July 2013 (1)

- June 2013 (1)

- May 2013 (1)

- April 2013 (1)

- March 2013 (1)

- February 2013 (2)

- January 2013 (2)

- December 2012 (1)

- November 2012 (2)

- October 2012 (2)

- September 2012 (1)

- August 2012 (2)

- July 2012 (2)

- June 2012 (1)

- May 2012 (2)

- April 2012 (2)

- March 2012 (2)

- February 2012 (3)

- January 2012 (2)

- December 2011 (3)

- November 2011 (2)

- October 2011 (2)

- September 2011 (2)

- August 2011 (2)

- July 2011 (2)

- June 2011 (2)

- May 2011 (2)

- April 2011 (2)

- March 2011 (2)

- February 2011 (2)

- January 2011 (2)

- December 2010 (2)

- November 2010 (2)

- October 2010 (2)

- September 2010 (2)

- August 2010 (1)

- July 2010 (2)

- June 2010 (2)

- May 2010 (4)

- April 2010 (3)

- March 2010 (4)

- February 2010 (4)

- December 2009 (1)

- November 2009 (3)

- October 2009 (4)

Upcoming Retreats

7 – 9 March 2014

Langkawi

Yoga at sunrise by a beautiful sandy beach to a pampering session at the spa or a guided nature tour; not to be missed, the sunset yoga session at the yoga deck of our retreat centre amongst tropical trees, made lively with chirping birds, curious monkeys and fluttering butterflies.

weekend yoga retreat package

Comments (2)

Donna

I really enjoyed this – thanks for sharing, Dorothy!

Dorothy

Always a pleasure Donna:):)Hope youre doing fine….